Photography can be subjective art, a method of communication. Photography can be objective journalism, a historical record . . .

But primarily, it’s a method for memory. We take pictures to “capture” a moment, a person, a location. And the photography business is built around the importance of taking, protecting, printing and sharing these memories.

While the imaging industry often talks about “photo gifts,” I believe the main gift of photography is the boost it can give our memory. And yes, even though we call photographs “memories,” of course they actually serve as triggers for the real memories stored in our brain. A picture can open a doorway into that interior room full of recollections. As we get older, these tools for recall become ever more important.

As I mentioned in a previous column, I am writing a book, Photography & Memory, that explores how photography (as a business and as an activity) depends on the importance we place on recollection, and how much memory now depends on photos to awaken otherwise dormant or forgotten moments. For the book, I talked with a wide variety of experts, professionals and enthusiasts, and there are two main issues they all agreed on. The two primary improvements most of us need to make in order for photography to improve our lives are better habits and more metadata.

Better Habits to Avoid Missed Moments

Here’s irony for you. In the middle of writing a book about using photography to supplement your memory, I took my mother—who is losing her memory—to a party at my sister’s new job at a senior care facility. It was only when I was driving home that I realized I had not taken a picture the entire evening! Not of my mother, my sister, the facility, the other people I met that night. Not one!

It’s not an isolated incident. I know I barely remember what happened last week, and a year from now I’ll look back on 2014 and wonder what happened that year. And because I don’t have pictures to trigger the memories, the answer might very well be, “Nothing much.”

I hope instead to start taking pictures of most events and occasions—big and small, important or merely incidental—so that next year, next decade, I can look back and see something memorable.

The fact is, however, even though we have plenty of advanced, affordable cameras, even though we have a more-than-adequate imaging device with us at all times in our phone, we still often fail to capture the memory. Why is this?

One obvious-in-retrospect reason is that when something is so easy, there’s no urgency. We know we can take dozens of pictures at any time, and so we fail to take even one at the right time. And then—whoops! The event is over. I immediately regret it when this happens: I know I might not remember much even next week, without anything to prompt my recollection.

Taking a picture can be a challenge for another reason. While many people these days look at the pictures they take during the experience, for the rest of us taking and looking at pictures during the moment takes us out of the moment. So to avoid spoiling the here and now, we don’t capture anything for the future. Rather than forget to take a photo, we decide we want to enjoy the experience and not worry about being a photographer or memory keeper.

What can we do? Perhaps we can train ourselves to take a “visual note” at any event—just to have a daily record. Or we can develop a reflex where the emotions of an event trigger the need to take a picture—prompt us to want to remember it that way.

We can “reframe” the idea that taking a snapshot takes us out of the moment—or that we have to distance ourselves emotionally from the situation in order to record it—and instead experience and capture simultaneously. Better yet, the act of taking a picture can bring us even more into the moment by making us really focus on what’s going on.

And while we’re taking more photos, let’s ensure we take good, meaningful shots. It drives me crazy to see people take a photo of their dinner at a fancy restaurant. Why? Not because I don’t like looking at food, but because that’s the only shot they take! I want to yell at them, “In 10 years—heck, in one year—will you care what that food looked like? No. Will you remember who you enjoyed it with? Nope. Wouldn’t you rather remember that?”

In other words: take pictures of people, not food. Dinner companions, not dinner.

Context Is Crucial

As much as many of us like to pretend otherwise, our memories are very subjective and often inaccurate. And so, it can often be quite a surprise to see a year-old image for the first time in a while that shows something distinctly different from the picture in our mind. Almost as bad is when we look at a picture and have no idea what it’s about: Who is that, anyway?

As I previously noted, I was driving my mother home from a reception and realized I had not taken a picture the entire evening. At that moment, I picked up my phone and snapped a shot of my mother in the car, to at least have something. But the next day, looking at that photo, I realized that in years to come all the photo would prompt me to wonder was why my mom was in my car.

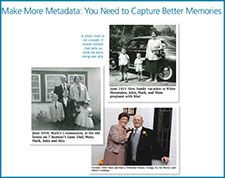

A photo itself is not enough. It needs context that tells us what we were doing and why. By itself, a picture can simply convey little if any information. We have to annotate it. We often say that a photograph is worth a thousand words, but the counterpoint is without a few words of context, the photograph can be all but worthless. Pictures of people and places we do not recognize have no meaning—and thus will not ever spark a memory.

Context and additional information are especially important when it comes to passing on pictures to future generations. Take that precious picture of your pop when he was a young man; unless it’s labeled, your descendants won’t recognize their ancestor, and the photo will hold no meaning for them.

At least many people in previous generations did write a name and a date on the back of a print. Today we have thousands of unlabeled images on a hard drive. We might think we’ve done our part if we keep our photographs organized by folders on a computer. I have one called “Trish’s Birthday, Bass Lake, 1997,” for example. But the images in that folder aren’t tagged in any way. If a shot is taken out of that folder, there’s no longer any context, description or other metadata adding meaning to that photograph.

This is an issue the industry can solve. As I noted in my previous column, I’ve often held my phone up at conferences and said, “This device knows who I am, where I am, the name of this event and even has access to information on who is attending—who all of you are in this room. Every photograph I take should be embedded with all of that information.”

Currently, no phone does that. No app has access to all of that information at once, or the ability to combine it all intelligently into a “smart photo.” But technologically, it is possible.

Until then, I look at people in pictures from last year and don’t even know who they are.